|

By Joe Hagan

From New York Magazine | Original Article

With a new master plan for the GOP, Karl Rove is revving up for a comeback.

Karl Rove is driving through Central Texas with his girlfriend, on the way to a weekend quail hunt.

“I’ve been called up by my emergency Texas militia unit to help stop an invasion of Texas blue quail in the Big Bend region,” he guffaws over a crackly phone line, somewhere outside Fredericksburg.

The man George W. Bush used to call Turd Blossom narrates the passing landscape—“The bottomlands are characterized by oak and mesquite, and the highlands are characterized by mountain juniper, a.k.a. cedar,” he drawls—and also takes a shot at the passing political scene: President Obama’s speech on the Tucson tragedy (“Good,” not “great”) and Sarah Palin’s video addressing the shooting (“I view it more as a lost opportunity than I do a seminal event”).

He even weighs in on a hot script circulating in Hollywood, College Republicans, about his own early years as a fresh-faced party apparatchik on the make. “They got it all wrong!” he says of the script, which he claims overemphasizes the importance of his onetime close colleague, Lee Atwater, the notorious strategist behind Bush 41. Perhaps Rove would consider consulting to set the record straight?

“For the right price, baby!” yells Rove, sending his gal pal into squeals of laughter.

“That’s my agent,” he quips.

The woman, Karen Johnson, is a lobbyist rumored to have been Rove’s mistress before his divorce from his second wife in 2009. When she tells him they’ve already reached the exit for Junction, Texas, Rove is impressed: “Goddangit, baby! We’re making good time!”

If Karl Rove is acting like a newlywed on a honeymoon, it’s no wonder: The proverbial Brain behind the most unpopular U.S. president in modern history, a man who feared he was on the verge of being charged with a felony in 2006 for his role in the Valerie Plame case, has a new lease on life. After reinventing himself as the resident political guru on two of Rupert Murdoch’s media platforms, Fox News and The Wall Street Journal op-ed page, Rove shocked everyone last year by putting together a political-action committee, American Crossroads, that, along with its sister organization, Crossroads GPS, raised $71 million to support Republicans during the midterm elections. The two groups spent nearly $25 million on 30,000 TV ads to attack Democrats and support Republicans, helping Rove’s party take sixteen of the 30 House and Senate seats in races where American Crossroads invested.

It was high-fives all around for Rove’s old crew. Without him, “we never, ever, ever would have been able to make the gains we made, which were historic,” says Mary Matalin, the onetime aide to former vice-president Dick Cheney.

“I concentrated some people’s attention,” Rove offers.

He’s just getting started. As he positions himself as Republican kingmaker in 2012, Rove is trying to make sense of a post-Bush party, one riven by ideological schisms and splintered into a dozen or more potential Republican nominees. To take back power and reestablish his dream of a permanent Republican majority (“Durable,” he now corrects. “I never said permanent”), Rove must carefully negotiate a new media world revolutionized by Sarah Palin and bring order to a restive party upended and realigned by tea-party populists, who view Rove as the elitist Machiavellian who once played them like a Stradivarius for George W. Bush. But with W. down on his ranch in Texas, the Brain needs a new body to inhabit. And that body, he’s decided, is the Republican Party itself.

When I first meet Karl Rove at his bachelor pad–cum–office in Georgetown on a cold morning in December, he’s buzzing like a guy who just leaped off the presidential helicopter a few seconds ago. Phone to his ear, he waves me inside while trying to connect to somebody named Grover. Two twentysomething female assistants, one the spitting image of Jenna Bush, scurry up and down the stairs, fetching tea and anything else Rove orders up.

“Kristin!” Rove yells to the Bush look-alike. “The day that Obama was in Bowie, Maryland, and attacks me—can you check it against my calendar and find out where I was?”

The Brain needs constant, multiple streams of data flowing in, raw information that he rearranges and reinterprets and then sends out to the appropriate destination to be acted upon. He was the first-ever White House employee to own a BlackBerry, making him the only e-mail-equipped staffer on Air Force One on 9/11. Information is power. When a text message pops up on his iPhone during our interview, lighting up his screen, I notice he’s surreptitiously taping our conversation with his field-recorder app.

His caution is understandable. Before he left the White House in 2007, the details of Rove’s conversations with reporters were the subject of five excruciating appearances before a federal grand jury, an inquiry into the infamous press leak of Valerie Plame’s identity as a CIA agent. That story became a referendum on Bush’s bloody war in Iraq and also on Rove’s secretive and brutal political style.

|

(Photo: Jacquelyn Martin-Pool/Getty Images; AFP/Getty Images; Roll Call/Getty Images; Alex Wong/Getty Images)

|

The ordeal took its toll. In his memoir, Courage and Consequence: My Life As a Conservative in the Fight, Rove writes of the stress of regular protests outside his D.C. home. He kept a newspaper clipping picturing Scooter Libby, Cheney’s chief of staff, as he was headed for his arraignment in the Plame case.

“I have looked at it frequently in the years since so as not to forget that moment,” he writes. “But for the work of a brilliant lawyer in unraveling and ending the quixotic obsession of a special prosecutor, there went I.”

Legal bills, he says, left him financially depleted. “Look, I had to worry about retirement,” Rove tells me, “and I had to worry about getting back to Texas.”

Rove also had a divorce on the horizon, from Darby, his wife of 24 years, which would mean the loss of more than half his assets. “The Karl I saw two years ago, maybe from a physical-exhaustion point, had a lower energy level than he does today,” says Jim Francis, a Republican operative in Dallas and a friend of Rove’s.

In August 2007, after more than six years inside the White House bubble, Rove was entering foreign terrain. In the intervening years, political media had morphed into a ravenous 24/7 spectacle, engulfing politics itself. And the instruments of Rove’s influence—George W. Bush and his network—were weakening quickly. By the time Barack Obama trounced Senator John McCain in 2008, it looked like a resounding end to the Rovean political era.

Modest though he may at times pretend to be, Rove has always seen himself as more than a glorified factotum. As he’s happy to remind you, he considers himself a policy intellectual, a man of letters who reveres Winston Churchill and posts his reading list on his website. Since the seventies, when he was a lonely college nerd—whose father, reportedly gay, left the family to an erratic mother who pocketed his school money and left Rove to fend for himself—bunking in a storage closet in a frat house in Utah, he’d been a self-made man. It took serious inner resources. The idea behind Bush’s nickname for Rove, Turd Blossom, was of a flower that grew from shit. With Democrats taking over Washington, Bush out to pasture, and his party in utter disarray, maybe Rove was actually in his element. He just needed a new horse to ride.

Not that it was going to be easy. First he had to refill his coffers. In the fall of 2007, Rove hired the ubiquitous D.C. lawyer Bob Barnett to set up a book deal and field calls from cable-TV networks. It was by “accident,” he says, that he ended up on Fox News. CNN initially began proposing a job and, says Rove, “tossing around figures that meant something.” Rove, who drove a titanium Jaguar to work when he was in the White House, says he was ambivalent about TV but needed cash. So he called up his friend Roger Ailes, who was about to step into a meeting with Rupert Murdoch. Fifteen minutes later, recounts Rove, he got a job offer from Fox. (Though a Fox spokesperson says that Ailes doesn’t recall that version of events.) He's paid roughly $400,000, less than half of Sarah Palin’s $1 million take. “But look,” he says, “they treat me well.”

Though Rove had not exactly been retiring in the past, he’d never been the front man either. But in the years he’d spent scheming in the White House, TV had become ever more important as one of the wellsprings of political power. It wouldn’t do just to be bright; he needed a brand and a platform. Being a media star would earn Karl Rove bigger speaking fees and better book sales and burnish his brand with political junkies; but most important, it would give him visibility with Republican donors, Rove’s true power source. In November 2008, Rove published a column in Newsweek, “A Way Out of the Wilderness.” Rove now points to that column as the genesis for American Crossroads. “What is it that Democrats have that we don’t have?” Rove says he asked himself.

What Democrats had was a massive money machine of well-organized political-action committees that had ground McCain to dust with TV ads and get-out-the-vote drives. For Rove, McCain’s hand-wringing over the influence of corporate money was all well and good, but money was the game, period. Rove has often been cast as the reincarnation of President William McKinley’s political adviser, Mark Hanna, who famously said there are only two things important in politics: money and “I can’t remember what the second one is.”

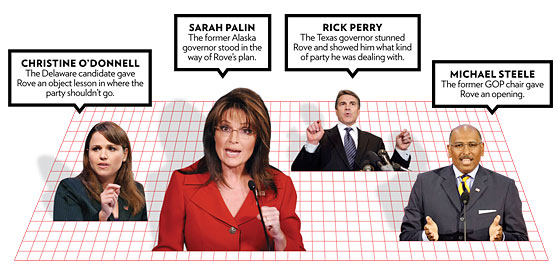

Raising money, like everything else in politics, works best if there are enemies, straw men, people to make you look like the only safe bet. Obama hadn’t been in office for six months when Rove saw a power vacuum with his name on it: Michael Steele, the head of the Republican National Committee, the traditional institutional center of the party, was swiftly losing credibility with party stalwarts, promising in interviews to give Republicans a “hip-hop” makeover and saying abortion was an “individual choice.”

|

(Photo: Karen Bleier/AFP/Getty Images)

|

Rove knew his party better than that, of course, and Steele’s tone-deafness was the opening he needed. Nervous donors, already suffering from the economic meltdown, were sitting on their money, uncertain where to go. In a series of meetings starting in the spring of 2009, Rove began sounding out the party’s big Republican underwriters, proposing an outside group that would effectively replace the RNC, featuring Karl Rove as the name brand on the label. He road-tested his sales pitch in Texas, he says, with old-line Bush donors like Katharine Armstrong, the ranch-and-real-estate heiress on whose family’s vast hunting grounds in South Texas Dick Cheney accidentally shot a lawyer in the face in 2006. Her land had long been Rove’s base of operations, where he shared a hunting lease with a top GOP fund-raiser in the state, James Huffines. There, Rove regularly plotted with Texas oil barons over a campfire, poking embers all night while working out strategy.

“He’s a pyromaniac,” says Armstrong, chuckling; she was duly swayed by Rove’s charm. “I said, ‘Karl, it’s a fantastic idea and you will do great and it needs to be done.’ He’s a very humble person. Sometimes it surprises me. ‘Karl, are you sure you’re not just fishing for a compliment? Or are you really insecure about this?’ ”

In truth, Rove didn’t have to work very hard. The prospect of Obama’s cap-and-trade policy was giving major heartburn to energy companies. “It’s like your doctor says you’ve got cancer and he pulls out a road map to recovery,” says Jim Francis, a close associate of billionaire oil magnate Trevor Rees-Jones, who gave $2 million to American Crossroads. “People were anxious to be supportive. And praying that it would work.”

Before Rove and his partner Ed Gillespie, the former counselor to Bush in the White House, had even slapped a name on it, American Crossroads had $25 million in commitments, mostly from patrons in Texas. To sweeten the deal, Rove said he wouldn’t take a dime for his efforts, acting only as an informal adviser, and hired as the group’s operator a well-regarded former Bush-administration official, Steven Law, who had been Senator Mitch McConnell’s chief of staff. That freed Rove to launch a separate but equally important campaign, the sort that’s become a staple of the modern campaign: the nonstop promotion of his new memoir, which sent Rove on a tour of 111 cities in 90 days, starting in March 2010. From January to November 2010, in between dozens and dozens of fund-raisers, paid speeches, and public readings, he wrote 61 op-ed columns, appeared on Fox News 83 times, and posted 1,400 tweets. His brand, and his bank account, were on the rise.

Rove, being Rove, doesn’t believe in post-Rove. “Things don’t change abruptly in politics.”

Last spring, Rove was ready to don the crown. He gathered the old tribes together and effectively anointed himself their leader, holding a breakfast at his house in D.C. with eighteen leaders of rival pacs, including former Nixon and Bush 41 confidant and GOP fund-raiser Fred Malek, of American Action Network, and Mary Cheney, Dick’s daughter, representing the Partnership for America’s Future. The anxious group was packed into Rove’s cramped living room, his two massive, ceiling-high shelves of history books looming over them. Rove, the man who had won big elections for them before and promised to win more again, let his star power do the work.

“They went so they could tell their friends that they went to Karl Rove’s house,” says Steven Law. “That’s why I went.”

Rove proposed they coordinate their strategies. American Crossroads would clearly have been first among equals; by default, Rove would be the figurehead, the credibility, the brand. Afterward, they would even give the meeting a self-consciously historic name, ready-made for the second volume of Rove’s memoirs: the Weaver Terrace Group, after Karl Rove’s street address.

In Karl Rove’s immaculate and thoroughly unlived-in apartment in Georgetown, one is struck by a display on a low table near the bookcase: scale models of Air Force One and Marine One, the Sikorsky helicopter that ferries the president to the White House lawn, right next to Rove’s baby shoes, lacquered white leather lace-ups, each embossed with his birthday, December 25, 1950.

As the virtual inventor of George W. Bush, Rove claims he has no real legacy of his own. “You know, I’m not allowed to have a legacy,” he says. “I just serve in the army, so it’s the army’s legacy.”

Bush and Rove remain a hand-in-glove operation. While there were always moments of tension between them, periods when Bush was agitated over the “Bush’s Brain” moniker, when Rove was in the doghouse over the Plame affair, Rove has remained Bush’s loyal courtier. Bush attended Rove’s 60th-birthday party in Austin last year, and Rove still regularly e-mails Bush political gossip he picks up in his travels. The two men were in close contact while they wrote their respective books, comparing notes on events.

“I said, ‘I’ll be happy to look at anything you want me to, but I don’t want to read it unless you need me to, because if it leaks, I don’t want people saying, ‘Rove had a copy of it,’ ” he explains. “And so we talked about it during the time. And of course he was reading parts of mine.”

Despite all this, Rove says Bush’s legacy would be “probably the same” without him. “There would have been somebody else,” he says.

Of course Rove has a legacy: Among other things, he politicized the White House like no other adviser before him. When I ask Rove about the unprecedented policy power afforded him, a campaign strategist who sliced and diced electoral data for a living, he won’t concede that it was particularly unusual, saying only, “It may have been different because I was sort of the mad scientist for the campaign and then I became the mad scientist inside the White House.”

Indeed: Earlier this year, the Office of Special Counsel reported that the White House political-affairs office, overseen by Rove, routinely broke an election law by conducting campaign strategy on the taxpayers’ dime.

The Bush era was also marked by lockstep message discipline among Republicans. But when the Bush White House disbanded, cracks in the façade appeared everywhere. Dick Cheney, we now know, remains bitter over Bush’s decision not to pardon Scooter Libby. Rove, avoiding the topic entirely in his book, says he supported Bush’s decision to let Libby hang. Asked if he ever offered Libby his condolences, given their similar predicaments and vastly different fates, Rove only says, “Scooter’s my close friend, and I think the world of him.”

Rove, too, left plenty of hurt feelings among former Bush staffers, several of whom told me Rove kept a tight grip on access to Bush, making himself the bottleneck for information traveling up the chain of command. Prominent Bush aides like Karen Hughes, Matthew Dowd, and Dan Bartlett have privately groused that Rove failed to credit them for contributions to Bush presidential elections and in managing the White House message machine. Laura Bush, wary of Rove’s influence, hinted publicly of this in a 2004 New York Times interview: “ ‘His input is valued just about, you know, equally with a whole lot of other people and—or maybe less, I should say, than some of the other people over there.’ ”

But few are willing to openly cross Rove, even today. He values loyalty above everything—to Bush and to him. Many of his colleagues describe him as a genuine and loyal friend, a good-humored and fun-loving pal who hands out cupcakes at meetings, sings ludicrously upbeat songs in the morning, and remembers everybody’s birthday. He even arranged to have a get-well note from President Bush sent to John Weaver, Rove’s former ally turned major antagonist, when Weaver was diagnosed with leukemia.

Some of these same friends, however, question whether Rove’s warmth is genuine or just good business. “Is it real?” wonders one person who worked closely with Rove for over a decade. John Weaver, for one, didn’t believe it was: He says he received a press call from NBC News’ Campbell Brown about Bush’s note two days before it actually arrived in the mail.

One week before the 2010 midterm elections, Rove took aim at Sarah Palin, questioning the wisdom of her appearance on a reality show, Sarah Palin’s Alaska, if she really wanted to be taken seriously as a presidential candidate. Palin lacked the “gravitas” to be president, went a subhead in the U.K.’s DailyTelegraph.

Rove later tried wriggling out of his comments, as well as observations he made in a German magazine that tea-partiers weren’t “sophisticated,” being unfamiliar, as Rove was, with intellectuals like the economist Friedrich August von Hayek. But Rove’s backhands weren’t accidental, nor was he the victim of outrageous tabloid reporting. When I bring up his statements about Palin during our interview, Rove says only that he wished he’d made his comments on Fox News instead—before going into a withering impersonation of Palin, recalling a scene from her TV show in which she’s fishing.

“Did you see that?” he says, adopting a high, sniveling Palin accent: “ ‘Holy crap! That fish hit my thigh! It hurts!’ ”

“How does that make us comfortable seeing her in the Oval Office?” he asks, disgusted. “You know—‘Holy crap, Putin said something ugly!’ ”

Rove was the first major Republican figure to take a swipe at Palin. But he knew he had to do it. A few months earlier, in Rove’s traditional seat of Texas, he had gotten an up-close view of the internal divisions threatening his place in the party’s firmament. Governor Rick Perry’s political machine was courting the new hard-right populists in tricornered hats, feeding rumors of presidential designs, and threatening to blot out Bush’s footprint on the state. The Bush family, for political and personal reasons, tried to unseat Perry, backing Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison in the Republican gubernatorial primary. Their best man was on the case: Karl Rove, who supported and reportedly advised Hutchison.

What resulted was a preview of the GOP–versus–tea party civil war. Dave Carney, Perry’s top strategist, attacked Rove as a “country club” Republican. Conversely, Sarah Palin, tea-party heroine, endorsed Rick Perry, calling him a “true conservative.”

Perry handily destroyed Hutchison in the primary.

“The Bushes are out of contact with what Texas is about,” says a veteran Republican politico who is close friends with Rick Perry. “So is Karl.”

Rove is the embodiment of everything the tea party resents. He supported Bush’s decision to bail out the banks in 2008, a major bone of contention with deficit hawks. And it was Rove, as White House political adviser, who pushed for some of the most expensive Bush programs, like the Medicare-prescription-drug bill, the passage of which cornered the troublesome State of Florida for Bush in 2004 but has already cost more than $1 trillion. The national debt nearly doubled under Bush, from $5.7 trillion to $10.6 trillion.

Rove knew he had to inoculate himself against tea-party insurrectionists if he was to keep his footing in the party. So his first, and defining, strategy idea for American Crossroads was to support a tea-party candidate in a marquee race: Sharron Angle, she of the “Second Amendment remedies,” against Democratic majority leader Harry Reid.

The investment was a classic Rovean gambit, a heads-I-win-tails-you-lose wager that put his new organization in the center of the action and on the right side, whichever side triumphed. If Angle won, American Crossroads had a huge Democratic pelt on the wall. If she lost, as she would, Rove’s skepticism of the tea party’s fringier elements would be proved correct. The bet was hedged. Rove, a realist prospecting for winners, his eyes fixed firmly on 2012, knew the deep-red base couldn’t win independents in a national race. As a former White House official who worked closely with Rove says, “Karl Rove is not a conservative. Karl Rove is a man who wins elections.”

"Holy crap!” says Rove, imitating Sarah Palin. “That fish hit my thigh!”

Then the Brain picked another no-brainer. In Delaware, where Obama’s health-care bill polled relatively well compared with other states, Rove had been supportive of centrist Republican Mike Castle. Castle was soundly beaten in the primary by tea-party insurgent Christine O’Donnell, whose colorful past, including a dalliance with witchcraft, exploded in the media. Rove shocked fellow Republicans by attacking her candidacy on Fox News. “It does conservatives little good,” he said, “to support candidates who, at the end of the day, while they may be conservative in their public statements, do not evince the characteristics of rectitude and truthfulness and sincerity and character that the voters are looking for.”

Blowback was swift. A baffled Rush Limbaugh observed that if Rove “had just gotten this mad at Democrats during the Bush administration, why, who knows how things would be different today.”

But Rove was only ramping up. And when he swiped at the tea party in October, Limbaugh homed in like a laser on what he saw as Rove’s self-serving motives, saying that “nobody who makes a living generating political support, generating political donations, nobody in that business can point to the tea party and say, ‘I did it.’ So it’s a threat.”

Mike Huckabee, also expressing disappointment with Rove, went on a rant about GOP “elites” who were trying to keep out the riffraff.

Later, however, when O’Donnell lost, the Brain collected his winnings. To Huckabee’s comments, Rove crows, “That’s not what he said when he immediately sent me an e-mail and said he was misquoted!”

I ask Rove if he actually believed Huckabee.

“Look, Huckabee is a populist,” he says, “which means it’s convenient for him to find somebody to position himself in opposition to, but the fact of the matter is Huckabee is a presidential candidate who ran well in the early primaries and scores well in the presidential sweepstakes for 2012. If there’s an Establishment, Huckabee is part of it.”

When I first mention the words “Republican Establishment,” Rove heatedly dismisses the idea as a “crackpot notion right up there with the Bilderbergers and the Trilateral Commission.” The Republican factions involved in picking presidential nominees are too large and bumptious a group to make an imagined country-club cabal meaningful, he says.

“You could talk about an Establishment in the nineteen twenties, thirties, and forties, when the bosses got together and chose who the candidate for governor was going to be,” explains Rove. “But that ain’t the way that it operates.”

For the better part of a year, it’s been a truism that whoever wins the Republican nomination must somehow defeat, or at least co-opt, Sarah Palin or the forces that she represents. Rove took up the challenge both for tactical reasons and because Palin represents something dangerous to Karl Rove: political chaos.

“That’s the part that Karl doesn’t like,” says Tom Pauken, a conservative Republican in Texas who has been a longtime Bush antagonist and specifically a critic of Rove. “This whole tea-party thing, he can’t control.”

The Rove-Palin polarity isn’t just about ideology; it’s about the merger of politics and media, how it changes the form and function of politics itself and threatens to shift power away from power brokers like Karl Rove. Rove is skeptical of Palin’s TV show as a smart political move, but he’s just as disgusted that Palin didn’t go to Delaware to support O’Donnell’s candidacy.

“And why?” he says. “ ’Cause she’s off for God knows how many weeks, during the summer of a vital election year, in which candidates and party organizations are crying for her presence in races in order to raise money and visibility, and she’s spending—whatever—June, July, August, in Alaska doing a travelogue reality show.”

He says Palin’s people responded to his criticisms by suggesting they’d found a new way to campaign.

“Some of her people have talked to me and said, ‘Look, the old rules don’t apply,’ ” says Rove. “In essence, the candidate is the message. We’ll see. That’s an interesting view, and we’ll see how accurate it is.”

By operating without filters in a flattened media environment, Palin and the tea party have argued that power is now bottom-up, divorced from the top-down organizing structures Rove has functioned within for more than 30 years.

“For good and for ill, the party is becoming less institutionalized and more about personalities,” observes Steven Law. “With the decline of the Republican National Committee, the role that Sarah Palin has, the role that Karl has—it’s becoming somewhat personality, and not just personality but individual people: driven entrepreneurs, as opposed to institutions.”

This means that not only do Rove and Palin have loudspeakers, but so do gamier elements of the right-wing spectrum, like the “birthers” who believe that Obama wasn’t born in the U.S. That’s put Rove in the position of having to play flag man on a busy tarmac, trying to steer his party away from the unelectable fringe. A few prominent Republicans I spoke with, especially former Bush officials, were thrilled that Rove finally said aloud what many were thinking: Palin was an embarrassment, even a threat to the party’s path back to power.

“He deserves a medal,” says one Republican operative who is friends with Rove. “This is a guy who understands what’s involved in being commander-in-chief. He looks at Sarah Palin and says, ‘Are you fucking kidding me?’ ”

Meanwhile, however, Rove’s close friend and ally Mitch Daniels, the Indiana governor and former Bush budget director who many believe Rove would like to see nominated, enraged the party’s base by suggesting a “truce” between centrists and the far right, with some factions protesting his appearance at the recent Conservative Political Action Conference.

This is clearly unsettling for Rove, the self-taught historian of American politics who cut his teeth doing direct mail for campaigns, which shaped his view of the electorate as slivers of demographics to be divided and conquered with carefully manicured wedge issues like gay marriage. The shock-news approach of Palin and Michele Bachmann and pretty much every other Fox News candidate, which pegs TV ratings to polling and, perhaps, to votes, is anti-Rovean, possibly post-Rovean. And Rove, being Rove, doesn’t believe in post-Rove. “Things don’t change abruptly in politics,” he says.

For the moment, with Palin’s star dimming, Rove is looking, for now, like a winner. The old ways, if he can help it, will stand. And this puts Rove in a place he dearly loves to be: not merely in a position of power but also on the high moral ground, a place of … Courage and Consequence. It even allows Rove—Karl Rove!—to wonder aloud how politics got so lousy, so much like Sarah Palin. For the past few years, he says, he’s actually been stroking his chin over the question of who’s responsible for the coarsened state of politics: the attention-seeking politicians or the media that encourages them to goose their ratings?

“I don’t have a conclusive answer,” he says. “I got a prospective answer, which is it’s the politicians.”

“I want to go on the record saying definitively that I wasn’t even born at the time of the Roswell incident!”

Karl Rove, nearing the quail, is considering some of the recent headlines about himself, like the report that he’s been advising the Swedish prime minister and is secretly behind the prosecution of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, part of an effort to stop leaks of Bush-era secrets that would expose Rove’s nefarious dealings.

“No, that’s a complete fabrication,” he says.

A lot of Rove’s friends tell me he’s misunderstood. Even enemies say so. Rove is not evil, says former Bush campaign strategist and apostate Matthew Dowd, nor is he a genius. Instead, he says, Rove is a self-marketer of his own reputation.

“What happened in 2010 had nothing to do with Karl and nothing to do with American Crossroads and everything to do with the political environment,” Dowd says. “Karl maintains a lot of the myth in a world not based totally in facts.”

The same, he says, goes for the 2012 presidential election. “The reason why a Republican is nominated won’t be because of Karl,” he says. “That doesn’t mean he won’t create a narrative.”

But creating a narrative is perhaps Rove’s greatest talent. He rewrote a Connecticut blue blood as a Texas good ol’ boy, a persona Rove himself inhabits like a Method actor, gamely dropping red-state signifiers like “Git’r done!” And as Republican candidates come and go, Rove will act as a narrator on TV while he kicks up millions for American Crossroads.

But Rove’s machine is already facing a competing brand: the Koch brothers, David and Charles, the major tea-party underwriters who are promising to raise $88 million for the presidential elections, posing a populist alternative to Rove’s Establishment stronghold and making inroads with their support of Governor Scott Walker in Wisconsin and funding of counterprotests there. It’s not inconsequential: Major Republican donors told me they were disappointed by Rove’s comments about Palin. “He’s not right all the time,” one of them noted.

In theory, Koch’s group and Rove’s group could form an unholy alliance in a general election. But Rove very clearly leaves the door open to an intervention in the primaries, before a nominee is actually chosen. If his Crossroads donors object to a candidate they don’t believe could take the general election against Obama, he says, Rove’s group might step in.

“Yeah, I could see that,” says Rove. “Right now, I don’t think it’s gonna happen, but I could see it. But again, this thing is gonna play out.”

Rove declines to say whether he’d advise a candidate in the primaries. But Mary Matalin paints the candidates as sorry losers clawing at Rove’s door.“There is not one of those twelve wannabes who wouldn’t cut off an arm to have Karl be their architect,” she says. “They’d take rumbling from some of their flank. But I defy any one of them to say, ‘If Karl was available to be my consultant on my 2012 race, I would decline his assistance.’ ”

But something like the opposite might be true. Does the next candidate of the GOP want the mark of “Bush’s Brain” on their candidacy? To alienate the tea party by cozying up to the elitist Rasputin?

Certainly not Sarah Palin. “Of all the potential candidates, Governor Palin would no doubt be the one desiring new energy and ideas,” says her chief of staff Michael Glassner, “and, refreshingly, hiring advisers who aren’t entrenched in any political machine.”

It’s early yet, and Rove is keeping his cards close and his options open. When I ask him which of the prospective candidates is the purest ideological heir to Bush, he won’t answer. “I don’t think that’s the right question,” he says, waving it away. But later, in an unscripted moment worthy of Palin, Rove does tell me about his dream candidate, a would-be “incredible” president of the United States, the one person he’d support without reservation, if only this man were running for the White House. Somebody who would set the world aright for Karl Rove.

Name of Bush. Jeb Bush.

|