|

By Nicolas J.S. Davies

From Consortiumnews.com | Original Article

The numbers of casualties of U.S. wars since Sept. 11, 2001 have largely gone uncounted, but coming to terms with the true scale of the crimes committed remains an urgent moral, political and legal imperative, argues Nicolas J.S. Davies, in part two of his series.

In the first part of this series, I estimated that about 2.4 million Iraqis have been killed as a result of the illegal invasion of their country by the United States and the United Kingdom in 2003. I turn now to Afghan and Pakistani deaths in the ongoing 2001 U.S. intervention in Afghanistan. In part three, I will examine U.S.-caused war deaths in Libya, Somalia, Syria and Yemen. According to Ret. U.S. General Tommy Franks, who led the war against the Taliban in Afghanistan in reaction to 9/11, the U.S. government does not keep track of civilian casualties that it causes. “You know, we don’t do body counts,” Franks once said. Whether that’s true or a count is covered up is difficult to know.

As I explained in part one, the U.S. has attempted to justify its invasions of Afghanistan and several other countries as a legitimate response to the terrorist crimes of 9/11. But the U.S. was not attacked by another country on that day, and no crime, however horrific, can justify 16 years of war – and counting – against a series of countries that did not attack the U.S.

As former Nuremberg prosecutor Benjamin Ferencz told NPR a week after the terrorist attacks, they were crimes against humanity, but not “war crimes,” because the U.S. was not at war. “It is never a legitimate response to punish people who are not responsible for the wrong done.” Ferencz explained. “We must make a distinction between punishing the guilty and punishing others. If you simply retaliate en masse by bombing Afghanistan, let us say, or the Taliban, you will kill many people who don’t believe in what has happened, who don’t approve of what has happened.”

As Ferencz predicted, we have killed “many people” who had nothing to do with the crimes of September 11. How many people? That is the subject of this report.

Afghanistan

In 2011, award-winning investigative journalist Gareth Porter was researching night raids by U.S. special operations forces in Afghanistan for his article, “How McChrystal and Petraeus Built an Indiscriminate Killing Machine.” The expansion of night raids from 2009 to 2011 was a central element in Barack Obama’s escalation of the U.S. War in Afghanistan. Porter documented a gradual 50-fold ramping up from 20 raids per month in May 2009 to over 1,000 raids per month by April 2011.

But strangely, the UN Assistance Mission to Afghanistan (UNAMA) reported a decrease in the numbers of civilians killed by U.S. forces in Afghanistan in 2010, including a decrease in the numbers of civilians killed in night raids from 135 in 2009 to only 80 in 2010.

U.S. Marines patrol street in Shah Karez in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, on Feb. 10. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Staff Sgt. Robert Storm)

UNAMA’s reports of civilian deaths are based on investigations by the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC), so Noori Shah Noori, an Afghan journalist working with Porter on the article, interviewed Nader Nadery, a Commissioner of the AIHRC, to find out what was going on.

Nadery explained to Noori, “…that that figure represented only the number of civilian deaths from 13 incidents that had been fully investigated. It excluded the deaths from 60 other incidents in which complaints had been received, but had not yet been thoroughly investigated.”

“Nadery has since estimated that the total civilian deaths for all 73 night raids about which it had complaints was 420,” Porter continued. “But the AIHRC admits that it does not have access to most of the districts dominated by the Taliban and that people in those districts are not aware of the possibility of complaining to the Commission about night raids. So, neither the AIHRC nor the United Nations learns about a significant proportion – and very likely the majority – of night raids that end in civilian deaths.”

UNAMA has since updated its count of civilians killed in U.S. night raids in 2010 from 80 to 103, still nowhere close to Nadery’s estimate of 420. But as Nadery explained, even that estimate must have been a small fraction of the number of civilian deaths in about 5,000 night raids that year, most of which were probably conducted in areas where people have no contact with UNAMA or the AIHRC.

As senior U.S. military officers admitted to Dana Priest and William Arkin of The Washington Post, more than half the raids conducted by U.S. special operations forces target the wrong person or house, so a large increase in civilian deaths was a predictable and expected result of such a massive expansion of these deadly “kill or capture” raids.

The massive escalation of U.S. night raids in 2010 probably made it an exceptional year, so it is unlikely that UNAMA’s reports regularly exclude as many uninvestigated reports of civilian deaths as in 2010. But on the other hand, UNAMA’s annual reports never mention that their figures for civilian deaths are based only on investigations completed by the AIHRC, so it is unclear how unusual it was to omit 82 percent of reported incidents of civilian deaths in U.S. night raids from that year’s report.

We can only guess how many reported incidents have been omitted from UNAMA’s other annual reports since 2007, and, in any case, that would still tell us nothing about civilians killed in areas that have no contact with UNAMA or the AIHRC.

In fact, for the AIHRC, counting the dead is only a by-product of its main function, which is to investigate reports of human rights violations in Afghanistan. But Porter and Noori’s research revealed that UNAMA’s reliance on investigations completed by the AIHRC as the basis for definitive statements about the number of civilians killed in Afghanistan in its reports has the effect of sweeping an unknown number of incomplete investigations and unreported civilian deaths down a kind of “memory hole,” writing them out of virtually all published accounts of the human cost of the war in Afghanistan.

UNAMA’s annual reports even include colorful pie-charts to bolster the false impression that these are realistic estimates of the number of civilians killed in a given year, and that pro-government forces and foreign occupation forces are only responsible for a small portion of them.

UNAMA’s systematic undercounts and meaningless pie-charts become the basis for headlines and news stories all over the world. But they are all based on numbers that UNAMA and the AIHRC know very well to be a small fraction of civilian deaths in Afghanistan. It is only a rare story like Porter’s in 2011 that gives any hint of this shocking reality.

In fact, UNAMA’s reports reflect only how many deaths the AIHRC staff have investigated in a given year, and may bear little or no relation to how many people have actually been killed. Seen in this light, the relatively small fluctuations in UNAMA’s reports of civilian deaths from year to year in Afghanistan seem just as likely to represent fluctuations in resources and staffing at the AIHRC as actual increases or decreases in the numbers of people killed.

If only one thing is clear about UNAMA’s reports of civilian deaths, it is that nobody should ever cite them as estimates of total numbers of civilians killed in Afghanistan – least of all UN and government officials and mainstream journalists who, knowingly or not, mislead millions of people when they repeat them.

Estimating Afghan Deaths Through the Fog of Official Deception

So the most widely cited figures for civilian deaths in Afghanistan are based, not just on “passive reporting,” but on misleading reports that knowingly ignore many or most of the deaths reported by bereaved families and local officials, while many or most civilian deaths are never reported to UNAMA or the AIHCR in the first place. So how can we come up with an intelligent or remotely accurate estimate of how many civilians have really been killed in Afghanistan?

Body Count: Casualty Figures After 10 Years of the “War On Terror”, published in 2015 by Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR), a co-winner of the 1985 Nobel Peace Prize, estimated deaths of combatants and civilians in Afghanistan based on UNAMA’s reports and other sources. Body Count’s figures for numbers of Afghan combatants killed seem more reliable than UNAMA’s undercounts of civilian deaths.

The Afghan government reported that 15,000 of its soldiers and police were killed through 2013. The authors of Body Count took estimates of Taliban and other anti-government forces killed in 2001, 2007 and 2010 from other sources and extrapolated to years for which no estimates were available, based on other measures of the intensity of the conflict (numbers of air strikes, night raids etc,). They estimated that 55,000 “insurgents” were killed by the end of 2013.

In Afghanistan, U.S. Army Pfc. Sean Serritelli provides security outside Combat Outpost Charkh on Aug. 23, 2012. (Photo credit: Spc. Alexandra Campo)

The years since 2013 have been increasingly violent for the people of Afghanistan. With reductions in U.S. and NATO occupation forces, Afghan pro-government forces now bear the brunt of combat against their fiercely independent countrymen, and another 25,000 soldiers and police have been killed since 2013, according to my own calculations from news reports and this study by the Watson Institute at Brown University.

If the same number of anti-government fighters have been killed, that would mean that at least 120,000 Afghan combatants have been killed since 2001. But, since pro-government forces are armed with heavier weapons and are still backed by U.S. air support, anti-government losses are likely to be greater than those of government troops. So a more realistic estimate would be that between 130,000 and 150,000 Afghan combatants have been killed.

The more difficult task is to estimate how many civilians have been killed in Afghanistan through the fog of UNAMA’s misinformation. UNAMA’s passive reporting has been deeply flawed, based on completed investigations of as few as 18 percent of reported incidents, as in the case of night raid deaths in 2010, with no reports at all from large parts of the country where the Taliban are most active and most U.S. air strikes and night raids take place. The Taliban appear to have never published any numbers of civilian deaths in areas under its control, but it has challenged UNAMA’s figures.

There has been no attempt to conduct a serious mortality study in Afghanistan like the 2006 Lancet study in Iraq. The world owes the people of Afghanistan that kind of serious accounting for the human cost of the war it has allowed to engulf them. But it seems unlikely that that will happen before the world fulfills the more urgent task of ending the now 16-year-old war.

Body Count took estimates by Neta Crawford and the Costs of War project at Boston University for 2001-6, plus the UN’s flawed count since 2007, and multiplied them by a minimum of 5 and a maximum of 8, to produce a range of 106,000 to 170,000 civilians killed from 2001 to 2013. The authors seem to have been unaware of the flaws in UNAMA’s reports revealed to Porter and Noori by Nadery in 2011.

But Body Count did acknowledge the very conservative nature of its estimate, noting that, “compared to Iraq, where urbanization is more pronounced, and monitoring by local and foreign press is more pronounced than in Afghanistan, the registration of civilian deaths has been much more fragmentary.”

In my 2016 article, “Playing Games With War Deaths,” I suggested that the ratio of passive reporting to actual civilian deaths in Afghanistan was therefore more likely to fall between the ratios found in Iraq in 2006 (12:1) and Guatemala at the end of its Civil War in 1996 (20:1).

Mortality in Guatemala and Afghanistan

In fact, the geographical and military situation in Afghanistan is more analogous to Guatemala, with many years of war in remote, mountainous areas against an indigenous civilian population who have taken up arms against a corrupt, foreign-backed central government.

The Guatemalan Civil War lasted from 1960 to 1996. The deadliest phase of the war was unleashed when the Reagan administration restored U.S. military aid to Guatemala in 1981,after a meeting between former Deputy CIA Director Vernon Walters and President Romeo Lucas García, in Guatemala.

U.S. military adviser Lieutenant Colonel George Maynes and President Lucas’s brother, General Benedicto Lucas, planned a campaign called Operation Ash, in which 15,000 Guatemalan troops swept through the Ixil region massacring indigenous communities and burning hundreds of villages.

President Ronald Reagan meeting with Guatemalan dictator Efrain Rios Montt.

CIA documents that Robert Parry unearthed at the Reagan library and in other U.S. archives specifically defined the targets of this campaign to include “the civilian support mechanism” of the guerrillas, in effect the entire rural indigenous population. A CIA report from February 1982 described how this worked in practice in Ixil:

“The commanding officers of the units involved have been instructed to destroy all towns and villages which are cooperating with the Guerrilla Army of the Poor [the EGP] and eliminate all sources of resistance,” the report said. “Since the operation began, several villages have been burned to the ground, and a large number of guerrillas and collaborators have been killed.”

Guatemalan President Rios Montt, who died on Sunday, seized power in a coup in 1983 and continued the campaign in Ixil. He was prosecuted for genocide, but neither Walters, Mayne nor any other American official have been charged for helping to plan and support the mass killings in Guatemala.

At the time, many villages in Ixil were not even marked on official maps and there were no paved roads in this remote region (there are still very few today). As in Afghanistan, the outside world had no idea of the scale and brutality of the killing and destruction.

One of the demands of the Guerrilla Army of the Poor (EGP), the Revolutionary Organization of Armed People (ORPA) and other revolutionary groups in the negotiations that led to the 1996 peace agreement in Guatemala was for a genuine accounting of the reality of the war, including how many people were killed and who killed them.

The UN-sponsored Historical Clarification Commission documented 626 massacres, and found that about 200,000 people had been killed in Guatemala’s civil war. At least 93 percent were killed by U.S.-backed military forces and death squads and only 3 percent by the guerrillas, with 4 percent unknown. The total number of people killed was 20 times previous estimates based on passive reporting.

Mortality studies in other countries (like Angola, Bosnia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Kosovo, Rwanda, Sudan and Uganda) have never found a larger discrepancy between passive reporting and mortality studies than in Guatemala.

Based on the discrepancy between passive reporting in Guatemala and what the U.N. ultimately found there, UNAMA appears to have reported less than 5 percent of actual civilian deaths in Afghanistan, which would be unprecedented.

Costs of War and UNAMA have counted 36,754 civilian deaths up to the end of 2017. If these (extremely) passive reports represent 5 percent of total civilian deaths, as in Guatemala, the actual death toll would be about 735,000. If UNAMA has in fact eclipsed Guatemala’s previously unsurpassed record of undercounting civilian deaths and only counted 3 or 4 percent of actual deaths, then the real total could be as high as 1.23 million. If the ratio were only the same as originally found in Iraq in 2006 (14:1 – before Iraq Body Count revised its figures), it would be only 515,000.

Adding these figures to my estimate of Afghan combatants killed on both sides, we can make a rough estimate that about 875,000 Afghans have been killed since 2001, with a minimum of 640,000 and a maximum of 1.4 million.

Pakistan

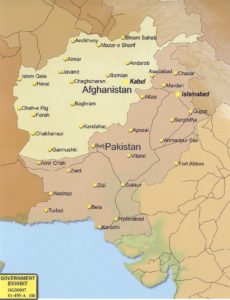

The U.S. expanded its war in Afghanistan into Pakistan in 2004. The CIA began launching drone strikes, and the Pakistani military, under U.S. pressure, launched a military campaign against militants in South Waziristan suspected of links to Al Qaeda and the Afghan Taliban. Since then, the U.S. has conducted at least 430 drone strikes in Pakistan, according to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, and the Pakistani military has conducted several operations in areas bordering Afghanistan.

Map of Pakistan and Afghanistan (Wikipedia)

The beautiful Swat valley (once called “the Switzerland of the East” by the visiting Queen Elizabeth of the U.K.) and three neighboring districts were taken over by the Pakistani Taliban between 2007 and 2009. They were retaken by the Pakistani Army in 2009 in a devastating military campaign that left 3.4 million people as refugees.

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism reports that 2,515 to 4,026 people have been killed in U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan, but that is a small fraction of total war deaths in Pakistan. Crawford and the Costs of War program at Boston University estimated the number of Pakistanis killed at about 61,300 through August 2016, based mainly on reports by the Pak Institute for Peace Studies (PIPS) in Islamabad and the South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP) in New Delhi. That included 8,200 soldiers and police, 31,000 rebel fighters and 22,100 civilians.

Costs of War’s estimate for rebel fighters killed was an average of 29,000 reported by PIPS and 33,000 reported by SATP, which SATP has since updated to 33,950. SATP has updated its count of civilian deaths to 22,230.

If we accept the higher of these passively reported figures for the numbers of combatants killed on both sides and use historically typical 5:1 to 20:1 ratios to passive reports to generate a minimum and maximum number of civilian deaths, that would mean that between 150,000 and 500,000 Pakistanis have been killed.

A reasonable mid-point estimate would be that about 325,000 people have been killed in Pakistan as a result of the U.S. War in Afghanistan spilling across its borders.

Combining my estimates for Afghanistan and Pakistan, I estimate that about 1.2 million Afghans and Pakistanis have been killed as a result of the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

Nicolas J.S. Davies is the author of Blood On Our Hands: the American Invasion and Destruction of Iraq. He also wrote the chapter on “Obama at War” in Grading the 44th President: a Report Card on Barack Obama’s First Term as a Progressive Leader.

|