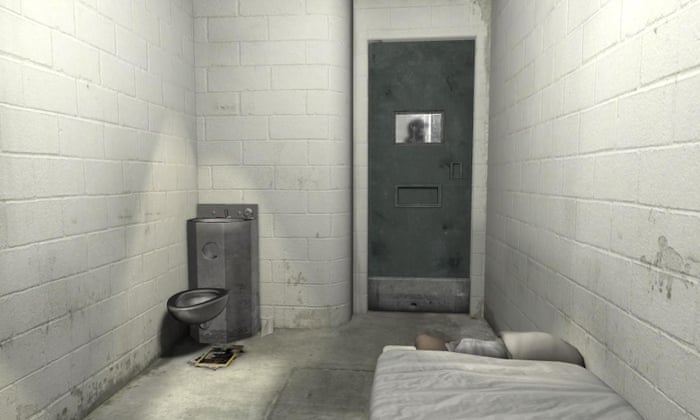

After a month on suicide watch, I was transferred back to US, to a tiny 6 x 8ft (roughly 2 x 2.5 meter) cell in a place that will haunt me for the rest of my life: the US Marine Corps Brig in Quantico, Virginia. I was held there for roughly nine months as a “prevention of injury” prisoner, a designation the Marine Corps and the Navy used to place me in highly restrictive solitary conditions without a psychiatrist’s approval.

For 17 hours a day, I sat directly in front of at least two Marine Corps guards seated behind a one-way mirror. I was not allowed to lay down. I was not allowed to lean my back against the cell wall. I was not allowed to exercise. Sometimes, to keep from going crazy, I would stand up, walk around, or dance, as “dancing” was not considered exercise by the Marine Corps.

To pass the time, I counted the hundreds of holes between the steel bars in a grid pattern at the front of my empty cell. My eyes traced the gaps between the bricks on the wall. I looked at the rough patterns and stains on the concrete floor – including one that looked like a caricature grey alien, with large black eyes and no mouth, that was popular in the 1990s. I could hear the “drip drop drip” of a leaky pipe somewhere down the hall. I listened to the faint buzz of the fluorescent lights.

For brief periods, every other day or so, I was escorted by a team of at least three guards to an empty basketball court-sized area. There, I was shackled and walked around in circles or figure-eights for 20 minutes. I was not allowed to stand still, otherwise they would take me back to my cell.

I was only allowed a couple of hours of visitation each month to see my friends, family and lawyers, through a thick glass partition in a tiny 4 x 6ft room. My hands and feet were shackled the entire time. Federal agents installed recording equipment specifically to monitor my conversations, except with my lawyers.

The United Nations special rapporteur on torture, Juan Mendez, condemned my treatment as “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment”, describing “the excessive and prolonged isolation” I was placed under for that period of time. However, he didn’t stop there. In a preface to the 2014 Spanish edition of the Sourcebook on Solitary Confinement, written by Méndez he stronglyrecommends against any use of solitary confinement beyond 15 days.

As Mendez explains:

Prolonged solitary confinement raises special concerns, because the risk of grave and irreparable harm to the detained person increases with the length of isolation and the uncertainty regarding its duration. In my public declarations on this theme, I have defined prolonged solitary confinement as any period in excess of 15 days. This definition reflects the fact that most of the scientific literature shows that, after 15 days, certain changes in brain functions occur and the harmful psychological effects of isolation can become irreversible.

Unfortunately, conditions similar to the ones I experienced in 2010-11 are hardly unusual for the estimated 80,000 to 100,000 inmates held in these conditions across the US every day.

The evidence is overwhelming that it should be deemed as such: solitary confinement in the US is arbitrary, abused and unnecessary in many situations. It is cruel, degrading and inhumane, and is effectively a “no touch” torture. We should end the practice quickly and completely