|

By Deborah Kory

From Huffingtonpost.com | Original Article

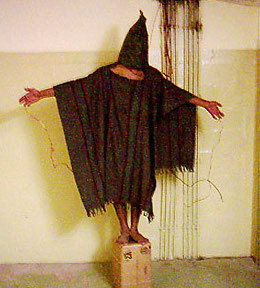

The recently released Hoffman Report, the independent investigation conducted by former Inspector General of Chicago David Hoffman into the American Psychological Association's (APA) collusion in the torture of prisoners at Guantanamo and other CIA "black sites," has sent shock waves through the psychology profession, whose members are not at all happy to be the public face of torture in America. Listservs around the country are erupting with consternation and outrage, with demands for accountability and justice and reform and cries of betrayal. Our profession is in a full-blown crisis and psychologists around the country are confused, embarrassed, unsure of how to respond in a meaningful way.

What shocks me is how shocked my professional community suddenly seems to be, since much of the information in the Hoffman report has been available to the public for many years, thanks to the ceaseless work of activist psychologists like Steven Reisner, Stephen Soldz, and Jean Maria Arrigo, who first blew the whistle on the APA's cover up back in 2006. Arrigo had participated in APA's bogus Presidential Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security, known as the PENS Task Force, which sought to investigate the ethics of "enhanced interrogation" (torture) by appointing a panel made up almost entirely of military personnel who had direct experience with torture at one or more of the various CIA black sites. They, and a small handful of other psychologists out on the frontlines of this battle have been intimidated, publicly maligned, and marginalized by the APA in their attempt to discredit their critics and deflect attention from their dirty secrets.

I was a doctoral student in clinical psychology when news first broke about psychologists' involvement in torture. I had entered my studies with such optimism and hope about my career, feeling that I had finally found my home in the world--a vocation, not just a job--where I might make good use of my deep love and empathy for people and my desire to do some good in the world. It was shocking, then, to hear in my second year of training that people in my new profession were torturing people. I couldn't fathom how those people could be psychologists. Weren't we healers? Weren't we Carl Rogers and Virginia Satir and Freud and Carol Gilligan and...torturers? I couldn't wrap my head around it at all, so I decided to write my dissertation about it in order to get to the bottom of this incongruous debacle.

As I began to research the events around the torture of prisoners at CIA black sites, I discovered that financial embeddedness and collusion between the APA, the CIA and the Department of Defense spanned half of the last century, beginning with mind-control research at the start of the Cold War, then onto the torture of Vietnamese prisoners of war, CIA-backed training of torturers throughout Central and South America (at venues like the School of the Americas), and in a natural progression to the war on terror. The degree of entanglement between the military and the psychology profession, it turned out, was so longstanding, broad and deep that it would have been shocking had psychologists not been enlisted to prop up our latest war. (For more information on this sordid history, read Alfred McCoy's A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation from The Cold War to the War on Terror.)

Though people are utterly enraged at the actions of the American Psychological Association, let's remember the context in which these unscrupulous actions unfolded. Our President--no our entire government save one dissenter, Congressman Barbara Lee--decided that bombing, kidnapping, torturing and killing the civilian population of Afghanistan was an appropriate response to a terrorist attack on American soil. But much worse, our government decided that a "shock and awe" mass-murder approach to deposing Saddam Hussein, who had no connection to 9/11, was an appropriate sequel. Bush's legal counsel at the Department of Justice rewrote American law to circumvent constitutional and international law regarding treatment of prisoners of war. In short, this was a time of collective national insanity--not a diagnosis covered by insurance, mind you--and the APA was, for the first time, at the seat of absolute power.

Let's also remember that one of President Obama's first acts in office, besides not closing Guantanamo as he had promised, was to summarily reject the notion of investigating, much less prosecuting, the Bush Administration's crimes during the war on terror. This was a powerful signal to those at the APA that they could simply "look forward, not back," without fear of punishment. If our former President, and all of the president's men (and Condoleeza), could get away with lies, deception, torture and the murdering of civilians, why would these psychologists, this professional organization, bother to reckon with itself and its past?

What I struggle with today, as the "shocking" revelations finally seem to have penetrated the psychology profession and the public at large in a way they simply haven't over the last decade, is how to reckon with the intensity of our denial--as a nation, as a profession, as a collection of individuals struggling to make our way in the world. Even my socially progressive little graduate school in Berkeley, CA, received my research with indifference, with one administrator dismissing it as "totally insignificant," the concern of a couple of "ultra-lefties" with no relevance to our profession. This is Berkeley. We're supposed to be cultural revolutionaries in this town, and yet even here, the fact that the association that accredits and determines the curriculum for our training institutions was providing professional and legal cover for an illegal and deeply immoral torture program was deemed irrelevant. If that doesn't suggest a need for a radical overhaul of this profession, then this is not a profession I want to be a part of.

But I'm not turning in my shingle. What I know from this work is that crises of this nature open up the possibility of radical transformation. We psychologists--most of us at least--are loving people with big hearts and empathic natures and a desire to be instruments of healing and change. We are imaginative and inquisitive and have the capacity to hold many (sometimes too many) truths at once. But as we sort through the crisis in our midst, we must break free from thinking we are either confined or defined by this terribly dysfunctional professional organization. A change in leadership, changes to the ethics code, prosecution for those involved in illegalities, democratic checks and balances--these are essential acts of reparation. But to truly find our moral grounding again, nay to find our passion again, we must turn our sights beyond the APA and remember what it means to be healers, not just of individuals, but of society and the planet. If we put love of humanity at the center of our agenda, and reorganize our leadership, our ethics codes, our research and our training institutions around social, economic and ecological justice, putting aside once and for all the advancement of profession over people, we are sure to find our way.

Deb Kory is a psychologist in private practice in Berkeley, CA and the content manager for Psychotherapy.net

|