|

By Susannah York

From Revolution | Original Article

The Blood Telegram—Nixon, Kissinger and a Forgotten Genocide (Alfred Knopf, 2013) by Princeton University professor Gary J. Bass unearths the sinister role played by then President Richard Nixon and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in 1971 during Pakistan's nine-month slaughter of Bengali people in what was then East Pakistan, now Bangladesh. According to diverse sources, hundreds of thousands and maybe as many as three million people were killed. About 10 million refugees, mostly Hindu, fled to India, only to be kept in desperate camps where people died of starvation, lack of clean water and preventable diseases.

The Blood Telegram is an engrossing and revealing blow-by-blow account of the cynical—in fact criminal—diplomacy, as well as the often vicious back-biting and backstabbing, among the various actors: Nixon, Kissinger, Pakistan's ruling general Agha Yahya Khan, India’s leader Indira Gandhi and other Indian government officials, U.S. State Department figures and those representing the U.S. in Pakistan and India like Archer Blood. Author Bass combed through thousands of pages of recently declassified material from the Nixon Library, the National Archives of Washington and archives in India, interviews with White House staff, diplomats and Indian generals and previously unlistened-to and rather sordid White House tapes. Almost every paragraph of his book is footnoted, with 2,600 footnotes in total.

The book is up close and personal, revealing the immorality and baseness of especially Nixon and Kissinger, who knowingly and regularly lied to the public, the U.S. Congress and other governments and broke the laws they claimed to represent during the civil war between East and West Pakistan.

The American consul general in Dhaka, Archer Blood, sent many warnings of an impending bloodbath, saying that there was no chance of Pakistan holding together. Nixon's response was, "I feel that anything that can be done to maintain Pakistan as a viable country is extremely important." Kissinger commented, "Why should we say anything [to Yahya] that would discourage force [in East Pakistan]?"

Some Background

When India won its independence from Britain in 1947, Britain took advantage of divisions it had helped fan and other factors to split its former colony into two states based on religion, the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and primarily Hindu India. With the partition, as many as two million people died and 15 million refugees defined by their religious affiliations fled the land they had lived on for generations and flooded across each other's borders (Hindus living in Pakistan relocated to India and Muslims in India to Pakistan) to regions completely foreign to them.

This odd geographical creation born of contending reactionary interests combined different ethnic groups in both East and West Pakistan. There were Pashtuns, Punjabis and Baluchis in Western Pakistan who were mainly Muslim. East Pakistan was comprised of Bengalis and Biharis, a Muslim majority and sizeable Hindu minority. The partition of the British colony left both India and Pakistan devastated, claiming many lives in riots, rapes, murders and looting. This was the original crime that set the stage for the horrendous events of 1971.

The difference between East and West Pakistan was more than distance, the 1,500 kilometers of Indian territory that separated them. West Pakistan was economically much better off, contained the central government, the military institutions and tried to make Urdu the country's official language. East Pakistanis were majority Muslim and mainly spoke and saw themselves as Bengali. Urdu-speaking Bihari Muslims who moved to the East after partition were an exception. East Pakistanis were looked down upon by West Pakistanis. West Pakistan was only 25 million compared to 57 million East Pakistanis. From the beginning the question of the country's official language was an issue of great protest.

With independence from Britain, people in East Pakistan were initially loyal to the government in West Pakistan, but gradually felt that British colonialism had been replaced by West Pakistani domination. The West was suspicious of Bengalis and the Hindu minority in East Pakistan and saw them as pro-Indian. By 1958, the Pakistani generals imposed martial law in East Pakistan, banned political parties and made it impossible for Bengalis to voice their grievances.

Demands for more autonomy in the east were a constant. After two decades of statehood, opposition grew and many student and worker demonstrations pressed for autonomy. Facing a serious crisis of legitimacy, elections were finally granted by West Pakistan's military ruler, General Yahya.

The disastrous November 1970 Bhola Cyclone struck East Pakistan and the results fuelled outrage against West Pakistan. The devastation took the lives of 500,000 people in the low-lying area of East Pakistan. One witness recounted how after the 250 kilometre-an-hour winds, there was nothing to see but bodies of people and cattle strewn over the land. Some had been hurled 10 metres high into trees or out into the sea. Seen from a helicopter, the area hit by the storm looked like "a huge chocolate pudding dotted with raisins''—on closer view the awful realization was that the "raisins" were dead bodies.

President Nixon meets with President of Pakistan Yahya Khan. 1970. Photo: National Archives and Records Service

After the cyclone, General Yahya visited the area but was unmoved by the suffering and devastation. The almost total lack of support from the West Pakistani-based government created further enmity among East Pakistanis who endured this crisis. This helped lay the groundwork for the rebellion that was soon to take place. When elections finally did occur, Mujibur Rahman's Awami League in East Pakistan campaigned on promises of more autonomy so that East Pakistan could determine its own trade terms, issue its own currency and create a militia. General Yahya refused to accept the parliamentary majority won through the Awami League's landslide victory.

The U.S. consul general Blood, inspired by some of the Bengali nationalist outpourings in the street, believed that his government should intervene to prevent a massacre and hoped for a political solution. Talks were going on between the Eastern and Western politicians. Blood thought that Yahya was stalling until more of his army could be brought into East Pakistan. Blood sent repeated descriptions of the military build-up and the impending crisis, calling for the U.S. to intervene against it, all of which Nixon and Kissinger continued to ignore. Ships brim-full of armaments were unloaded in the port city of Chittagong despite efforts at a blockade by outraged Bengalis. On 25 March 1971 serious shooting began. There were major explosions throughout the city of Dhaka, and columns of troops marched through the city, with U.S.-supplied tanks in the lead. The civil war had begun.

The Blood Telegram

Two weeks into the slaughter in East Pakistan, angered over the silence by Nixon and Kissinger, Blood sent a five-page telegram signed by him and most of his staff denouncing the policy of the U.S. as "moral bankruptcy" for condoning the atrocities (which he called genocide because the killings were mainly against Hindu Bengalis) and the suppression of the election results, and the U.S.'s continued support and arming of General Yahya.

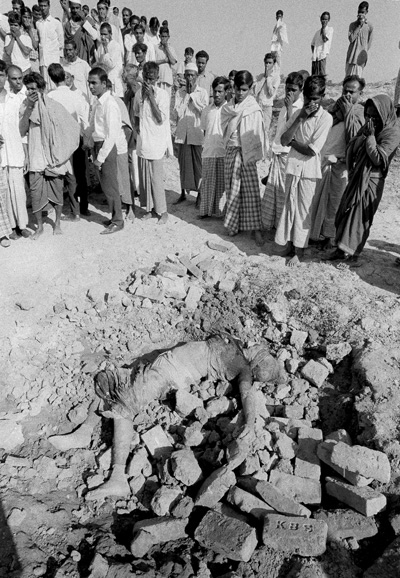

Bangladeshi massacre: Students, covering their faces from the stench of decaying bodies, uncover a mass grave containing the dead bodies of fellow students and professors near Dhaka, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), Dec. 1971. Photo: AP

The Blood telegram's content soon became public and gained credibility in various government circles. But Nixon and Kissinger were determined to continue supporting Yahya. Pakistan was already the recipient of billions of dollars worth of jets, bombers, armored tanks and military vehicles from the U.S. Seen as a traitor by Nixon and Kissinger, Blood was sacked and given a desk job in Washington.

Nixon rationalized what he deceitfully called U.S. non-action by comparing the situation in East Pakistan to the slaughter of Biafrans when they tried to secede from Nigeria in 1967-70, saying it would be hypocritical to intervene in Pakistan's internal affairs when the U.S. had done nothing in Biafra. Kissinger also tried to portray American policy as one of non-intervention. As the killings became more exposed, Congress imposed a ban on U.S. supplies of arms and military parts for Pakistan. To sidestep the law, Nixon and Kissinger quietly arranged with King Hussein of Jordan and the Shah of Iran for these countries to serve as conduits for American weapons and planes to the Pakistani military, with private assurances that there would be no penalty for breaking the ban. The Congressional ban on weapons shipments served as a smokescreen to hide what was really happening.

By late June, a New York Times reporter based in South Asia estimated that 200,000 people had died in East Pakistan and 154,000 refugees were fleeing daily. Meanwhile Nixon insisted that Yahya was a good friend and a decent man doing "a difficult job trying to hold those two parts of the country separated by thousands of miles and keep them together... it was wrong to assume that the U.S. should go around telling other countries how to arrange their political affairs."

Relations between Pakistan and India were already bitter since independence and the resulting partition. India had its own cold and calculating strategic concerns. It was engaged in a struggle with Pakistan over Indian efforts to annex Kashmir. Bass says that Indira Gandhi was concerned that rebellion in East Pakistan would encourage revolt in her own restive population due to the tremendous poverty of the people and their movements against the government. She also feared it might provide an opening for the Maoist Naxalite revolutionary movement then raging in the Indian state of West Bengal and elsewhere. Bass condemns her "lack of concern for human rights". This human rights prism prevents him from seeing Gandhi as the leader of a comprador (imperialist-dependent) exploiting class in league with the Soviet Union, which, despite its retention of some features of socialism—a planned economy and state ownership—had restored capitalism, become an imperialist superpower and was contending with the U.S. for world domination.

When East Pakistani refugees fleeing the massacres started pouring over the Indian border, Indira Gandhi tried to seize the moral high ground. Her government spoke emotionally about the millions of refugees. But privately it worried that the exiles might be revolutionaries and might not return to their own country. Among many in her government there was a clamour for war. Publicly Gandhi claimed India had no intention to go to war, but began training those East Pakistanis who wanted to take up arms—the Mukti Bahini (Liberation Army), initially under Indian leadership but eventually breaking out of its clutches. When she asked her generals how long it would take for the Indian army to be ready for war, they replied six months and began preparations.

Public diplomacy and much covert arm-twisting and threats took place between the U.S. and India. Both insisted that they were giving no support to the two sides in the war but behind the scenes they were not only preparing for all-out war between India and Pakistan but also trying to draw in China and the Soviet Union to take part on their respective sides. For reasons we will mention shortly, Kissinger secretly went to China to set up a meeting for Nixon with Mao Tsetung. While there, he called on the Chinese government, which considered Pakistan an ally against the Soviet Union and India (China and India had already engaged in armed conflicts twice), to send soldiers to the Chinese-Indian border and make trouble for India on its northern border should India go to war with Pakistan. Some Indian officials, on the other hand, were looking to the Soviet Union for military aid in case of an attack by China. And while preparing for war with Pakistan, Gandhi wanted to be sure that it looked like India was helping the Bengalis flee the massacres carried out by the West Pakistani army.

By the end of November a border clash and air battle took place, with Pakistan and India each blaming the other. From then on, the Indian Army launched increasing ground attacks into East Pakistan, denying it at the same time. On 3 December, Pakistan launched air strikes on India's major airfields in the north, in the states of Punjab, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. This gave Gandhi the excuse she wanted to launch a full-scale attack on Pakistan. The Indian army advanced quickly to capture Dhaka in the east. In a bitter rage, Nixon ordered a stop to all U.S. aid to India, branding the war Indian aggression. Kissinger called it "Indian-Soviet collusion, raping a friend of ours". Defeated, the Pakistani army signed a peace treaty on 16 December, ending the war and creating a new state, Bangladesh. A rapid growth of revolutionary communist forces occurred, along with a wide following among the masses and the development of some liberated areas outside the control of the various reactionary armies. (The complexity of what happened in Bangladesh during this period is not addressed in this review).

It is important that Bass's book has thoroughly exposed the little-known (outside South Asia) role played by Nixon and Kissinger in the Bangladesh war. By focusing on this particular event, he provides an eye-opening view of the sordid relations between reactionary governments that go on behind the scenes in the complex development of crises often of their creation and usually sealed from public view.

In an earlier book Bass argued for the need for humanitarian intervention to prevent or stop mass slaughters whenever they take place in the world. In The Blood Telegram, Bass argues they should have intervened to prevent the killing but instead pursued the policies they did for two reasons, the long-standing U.S. alliance with Pakistan and Nixon's personal friendship with its dictator General Yahya, and desire to not jeopardize Yahya's role in facilitating Nixon's hoped-for visit to China, seen as a major Cold War coup by Nixon and Kissinger.

But the book is missing a world context and leaves the U.S. government's pursuit of its national interests off the hook. Perhaps exceptional in their open baseness, still Nixon and Kissinger were not just two individuals. They were complicit in and facilitated the murder of East Pakistanis not mainly because of their subjective desires or personal immorality but the global interests that they were serving. They were leading representatives of the interests of an imperialist ruling class, the monopoly capitalists who rule the U.S. which before and since those events, have a long history of maintaining and seeking to expand a world empire of exploitation and oppression.

Bass's book calls Nixon and Kissinger's Bangladesh policy one of the worst crimes of the twentieth century and proves his point in great detail. Yet he ignores some of the evidence he himself brings to light, and especially the conclusions that this evidence objectively points to. In his preface he says that Nixon and Kissinger's "support of a military dictatorship engaged in mass murder is a reminder of what the world can easily look like without any concern for the pain of distant strangers." Yet while it is true that Nixon and Kissinger had no concern for Bangladeshi lives, they were extremely concerned about American imperialist interests. U.S. covert support for West Pakistan, on the one hand, and its public refusal to intervene to stop West Pakistan's slaughter in Bangladesh, on the other, were two sides of the same coin: the interests of maintaining and expanding the American empire in the face of Soviet rivalry for world domination.

The U.S. allied with Yahya's regime because the U.S. ruling class considered Pakistan a reliable ally in their efforts to "contain" (surround) the Soviet Union and counter Soviet-backed India. Nixon and Kissinger's pursuit of talks with China were based not only or even mainly on their personal ambitions but because of the same need for empire.

Bass wants to show that the U.S. should have intervened in Bangladesh on the side of human rights, and that Nixon and Kissinger's greatest crime was not allowing that to happen. He does not fully understand that intervention by the U.S. historically has only been and can only be for its own strategic interests and not for any humanitarian needs. Arguments about intervention or interfering in the internal affairs of a sovereign state have always been decided on the basis of the long and sometimes short-term goals of U.S. empire and not on moral grounds. In fact, as Bass documents extensively, in Bangladesh in 1971 Nixon and Kissinger did intervene, on the side that in their view best represented the global interests of the U.S.

The Importance of the Cold War

While nodding to the importance of the Cold War, Bass underestimates the collusion and especially contention between the U.S. and the Soviet Union as driving world events at the time. After World War 2, the Cold War went through many different phases. By the mid 1950's the Soviet Union was socialist in words, but in reality capitalist and imperialist. U.S.-Soviet contention over spheres of influence in Asia, Africa and Latin America led to a nuclear arms race and the increasing possibility of nuclear war.

Ironically, Nixon had been personally identified with the U.S. attempt to strangle the Chinese revolution early on, but, with the development of world events, he and Kissinger came to see the opening of channels with China as a strategic move in advancing American Cold War contention and shoring up of spheres of influence. At that time China, which was still a socialist country, was adopting certain tactical measures, including an "opening to the West," as part of dealing with the very real threat of attack on China by the Soviet Union. Formerly socialist allies, China had exposed the Soviet Union for becoming capitalist. There were intense skirmishes on the Chinese/Soviet border. Nixon and Kissinger understood this tension and thought by pursuing relations with China, they could have a tactical alliance with China against the Soviet Union.

The 1971 massacres and the 10 million refugees took place during a time when Nixon was propagating his "madman theory", by which the world was supposed to understand that he was insane enough to unleash nuclear weapons. Nixon and Kissinger threatened to use them against the Vietnamese. But the Vietnamese liberation struggle and other factors eventually forced Nixon to sign a peace accord. In 1973, the same Nixon/Kissinger government that publicly argued against intervention in Bangladesh organized a military coup against the elected government of Salvador Allende in Chile, seen as a threat to American interests to some degree because of U.S. fears that it would advance Soviet political influence in Latin America and elsewhere. Those events were fuelled by U.S.-Soviet Cold War contention. With the fall of the Berlin wall, the Cold War ended in a U.S. triumph. U.S. strategic goals were then to dismantle the Soviet bloc and establish itself as the sole superpower.

Don't Forget History

Beginning long before the Cold War and throughout the history of the United States, invasions, massacres, occupations, military coups, the use of nuclear weapons on civilian populations (in 1945) and threats to use them against many other countries, and the propping up of death squads and tyrants, have all been part of the fabric and historical foundation of the U.S. empire.

Over the almost 70 years following World War 2 the U.S. wantonly snuffed out millions and millions of lives—overwhelmingly civilians—often to terrorize and crush whole populations. It killed some three million with conventional weapons in South-east Asia during the Vietnam War, more than 500,000 through its backing and organizing of death squads in Central America in the 1980s, not to mention a continuation of such crimes when the Cold War no longer provided an excuse, such as the more than 500,000 Iraqis—mainly children—during the 1990s via the imposition of crippling economic sanctions, and the occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq. The interests of humanity and the lives of billions of people were nothing compared to considerations of empire.

What happened in Pakistan in 1971 is part of this, not a Nixon/Kissinger aberration. Nixon (who after his death has been somewhat exonerated by public opinion makers) and Kissinger (who despite his crimes is still highly regarded in imperialist circles) based all their actions principally on the basis of protection and expansion of U.S. empire and its spheres of influence.

Pakistan—a Tinderbox Made in the U.S.A.

Pakistan itself is an example of how the U.S. has used whole countries for its own interests and strategic objectives. For decades the U.S. saw it as a counterweight to India, which was allied with the Soviet Union. For much of its existence Pakistan has been ruled by military juntas that fostered Islamization as a foundation of their legitimacy, as a tool of state, and a means of suffocating the masses. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in the 1980s the U.S. stepped up military and economic support to Pakistan in order to aid Islamist opposition to the Soviets. Later the U.S. backed the Pakistani ISI (intelligence services) in helping bring the Taliban to power, which Pakistan saw as a way to ensure that Afghanistan stayed under its influence, instead of falling under that of India. Again, crimes lay the basis for more crimes.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the U.S. switched to cultivating India as its main ally in the region, causing increased rivalry between India and Pakistan. In the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan the U.S. drove the Taliban and other Islamists out of Afghanistan and into Pakistan and then further ignited hatred in both Afghanistan and Pakistan by its mass bombings of civilians and overall brutality of its occupation—illegally detaining and torturing both Pakistanis and Afghanis, using drone strikes and other military operations which kill many civilians.

Intervention by imperialist powers and other reactionary states, no matter in what guise, must be understood in this way. Intervention by the U.S. or any imperialist power will never bring about anything good. When thinking about Ukraine or Syria, people should remember what the U.S. did in Bangladesh.

|